PPC114 | Technical

Dr Alex Kent is Parasitology Lead in the Science and Laboratory Services Department (SLSD) of the Animal and Plant Health Agency (APHA).

His team is currently carrying out the UK’s annual Echinococcus multilocularis surveillance to confirm that the UK remains disease-free. Here he gives PPC readers a more detailed look at the disease, its effects, and why APHA monitors it.

Speed view

- Although rare, alveolar echinococcosis is a serious illness with an exceptionally high mortality rate

- E. multilocularis uses rodents or small mammals as hosts for the larval stages, which are then transmitted to wild canids ie foxes

- Since 2012, the annual E. multilocularis surveillance programme to confirm disease-free status in the UK has been carried out by APHA

- APHA needs pest controller collaboration in order to maintain a level of robust surveillance.

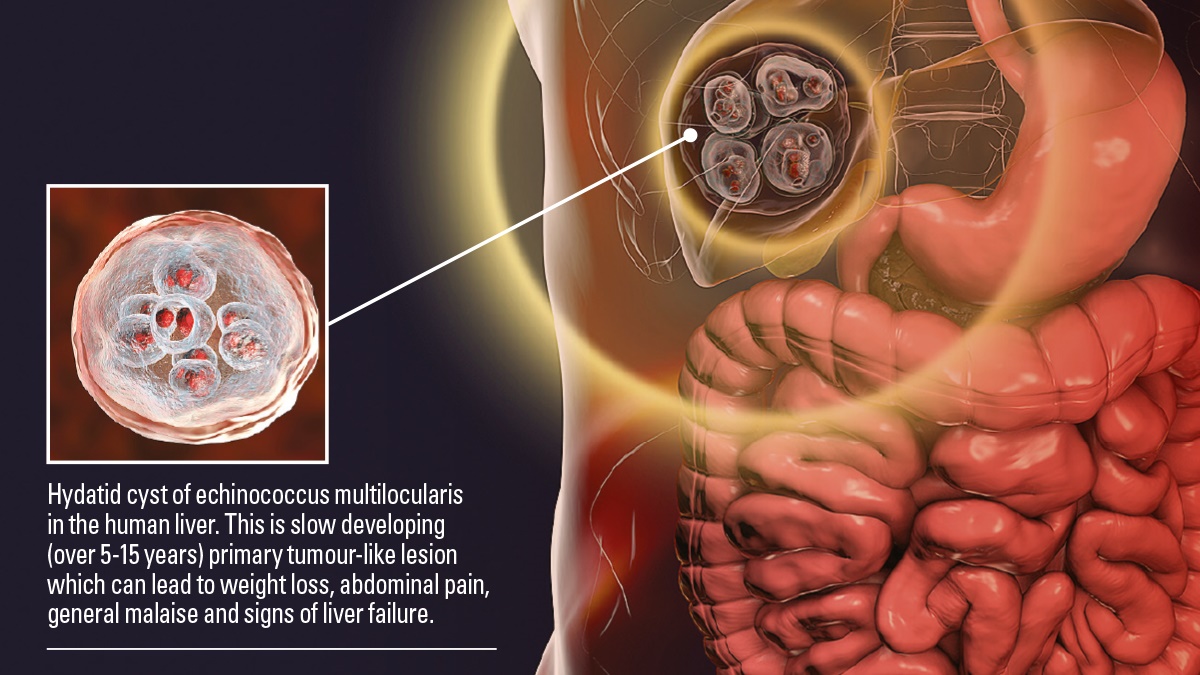

Human echinococcosis is a zoonotic disease (a disease that is transmitted to humans from animals) that is caused by parasites, namely tapeworms of the genus Echinococcus. Alveolar echinococcosis (AE) is a rare but serious infection caused by Echinococcus multilocularis.

Although some species of Echinococcus are present in the UK (Echinococcus granulosus – cause of cystic echinococcosis), the UK remains disease-free of E. multilocularis and, to-date, there have been no ‘internal’ AE cases.

However, AE was noted as the cause of death of a woman in 1954.

Despite never leaving the country, it was judged that the infection vector was regular consumption of unpasteurised cheese from an area in Switzerland endemically affected by E. multilocularis.

A further case was reported in 2002 in a man from Afghanistan who had recently moved to the UK from Pakistan.

Although uncommon, it is a very serious illness that requires monitoring. If untreated or if treatment is limited, AE results in a mortality rate of over 90% 10-15 years after diagnosis.

Parasites and pathways

Echinococcus multilocularis uses rodents or small mammals such as voles and lemmings as hosts for the larval stages, which are then transmitted to wild canids, particularly fox species, through ingestion.

It is in these hosts where larvae mature and reproduce, with each worm producing hundreds of eggs which are then released into the environment via faecal matter.

These eggs are ingested by rodents to begin the lifecycle again, but can also be transmitted to domestic dogs, occasionally cats and humans.

Human transmission can occur via three pathways: contact with eggs from either fox or dog faecal contamination in the environment, direct contact with eggs in dog faeces, or through contaminated dog hair while stroking the animal.

Historically, the risk of becoming infected by E. multilocularis in Europe was considered to be restricted to certain regions.

Until the 1990s for instance, only a ‘core’ area consisting of eastern France, southern Germany, parts of Switzerland and Austria were known to be endemic for the disease.

In recent years however, E. multilocularis has intensively spread into new areas including the Baltic, Denmark, the Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia and Sweden, becoming one of the most threatening parasitic challenges within Europe in the process.

The British Isles are fortunate to possess natural barriers which has helped prevent the introduction and establishment of E. multilocularis. However, there is a real risk of E. multilocularis being introduced through the legal importation of animals from other countries.

In May 2010, a female beaver was found floating in a pond on a country estate in the UK. Noting large cysts on the beaver’s liver, the owner froze it and subsequently sent the organ for testing.

The beaver had been wild caught in Germany in late 2006. Despite having been quarantined within the UK for six months, it was determined to be positive for E. multilocularis infection.

Despite this event, the legal importation of dogs remains the most likely route of introduction of E. multilocularis into the UK.

In 2011 for example, 85,786 dogs were imported to the UK but this has increased dramatically to 307,263 dogs in 2019, according to the Dogs’ Trust.

It has been estimated that, without treatment, there is a 98% probability that one dog in 10,000 would enter the UK carrying E. multilocularis.

Surveillance of a growing threat

In response, the European Commission (EC) adopted a regulation aimed to control E. multilocularis infection in dogs and decrease the potential risk of AE infection in humans.

This was to ensure continuous protection of Finland, Ireland, Malta and the UK – countries that have remained E. multilocularis ‘free’.

Specifically, this regulation put in place the foundations for the annual surveillance programme for the detection of E. multilocularis, which APHA has carried out since 2012.

As set out in the regulation, the programme must be able to detect a 1% prevalence in a representative host population with 95% confidence.

More specifically, the surveillance programme must include samples which reflect the geographical distribution of the UK’s red fox population, cover all 12 months of the year (excluding the cubbing season), and be of a sufficient size (over 383 faecal samples), based on the current estimate of the size of the population (approximately 357,000).

Funded by Defra, APHA has subsequently relied on a network of over 50 landowners, pest controllers and hunters who have supported the surveillance programme by providing more than 500 fox carcasses from mainland Britain on an annual basis.

All foxes undergo a post-mortem by the parasitology team, where faecal material is removed for the purposes of surveillance.

Additionally, we are also involved in providing a range of other samples to support a range of academic institutions carrying out research into life history, rodenticides, ticks, and other pathogens including Covid-19.

Now for the science-y stuff

Faecal samples are tested for E. multilocularis eggs by being combined with a zinc chloride solution, which enables any eggs to be isolated through flotation and sieving, and deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) is extracted from any eggs present.

Any DNA present is then combined with strands of DNA which contain unique sequences, to identify between E. multilocularis, E. granulosus and other Taeniid species.

These strands find the corresponding sequences within the DNA if present, which are then amplified. The resulting product is then separated by the size of the sequence using an electrical charge – also known as electrophoresis.

Sequences of DNA which have been amplified and separated can then be detected by fluorescence.

How pest controllers can help

Discovering the introduction of E. multilocularis on our shores as early as possible gives us the best possible chance to attempt to prevent further spread and potential eradication.

Furthermore, maintaining the UK’s disease-free status not only assists with the exportation of specific agricultural products, but also aids those of us who are pet owners.

For instance, the UK government has requested that the EU waive the requirement for a pre-movement tapeworm treatment for dogs imported from Great Britain.

The continuation of a robust surveillance programme for E. multilocularis is extremely important in multiple ways and without your collaboration, this simply would not be possible.

This is why we’re looking to increase our network of UK pest controllers who carry out fox control in urban areas.

All we ask is for your name, date of kill, postcode or grid reference and nearest town/village to be documented on each fox carcass.

Once recorded, we will collect these free of charge. We will also be able to supply any consumables needed for the surveillance eg bags, tags and cable ties.

Foxes can also be frozen until there are multiple carcasses for collection, as we try to be as cost-efficient as possible.

NEXT STEPS

If you are involved in the control of foxes in the UK and can help, please contact a member of APHA fox survey team:

Paul Cropper (northern England)

paul.cropper@apha.gov.uk

07496822408

Tim Glover (southern England)

tim.glover@apha.gov.uk

07713145682

For scientific queries please contact APHA Parasitology Lead:

Alex Kent

alex.kent@apha.gov.uk

07909646246

As a notifiable animal disease, you can also help with the UK’s ongoing surveillance by reporting any suspected infection immediately.

This can be done by calling the Defra Rural Services Helpline:

England 03000 200 301

Wales 0300 303 8268

Scotland – your local Field Services Office

Further information on how to spot E. multilocularis can be found at gov.uk/guidance/echinococcus-multilocularis-how-to-spot-and-report-the-disease