PPC115 | Technical

Dr Richard Naylor, from Cimex Store and The Bed Bug Foundation CIC, has studied bed bugs for over two decades. With his wife Alexia and team based near Chepstow, they run a bed bug R&D lab, testing products and culture insects for research and detection dog training. In this article, Dr Naylor shares insights from his studies and discusses the implications for bed bug management in 2024.

In 2019, you constructed two test bedrooms to evaluate bed bug products in a realistic environment. Why do you need them?

Bed bugs are inherently difficult to study. Once discovered, most people want them eradicated immediately, so there is usually no time to conduct any kind of meaningful field trial. Arena trials lack realism and, in particular, access to a host, which completely changes bed bug behaviour. A monitor might perform well in a small laboratory arena, but luring bed bugs in complex, room-scale environments, with a live host present, is quite different.

Our test bedrooms allow us to simulate infestations and conduct controlled, replicated experiments. They look like normal bedrooms with double beds, bedside tables, carpets and a window with a blind.

In one room, we have a wooden frame bed, and in the other, we have a divan-style bed, which has been fitted with an encasement to prevent the bugs from getting inside. Pitfall traps across the doorways prevent bugs from escaping from the rooms and allow us to see what impact the treatment is having on dispersal, which is always important to consider.

Over the past five years we have used this setup for testing traps, monitors, barrier tapes, bed isolation devices and insecticidal treatments.

“These bugs are given access to a human host (me) every week or so, to provide nourishment and to elicit the natural foraging and harbouring behaviour.”

One room is currently used for studies involving fixed numbers of bugs, which are released and later recaptured. Trials like this can last from 12 hours to more than six weeks, depending on what we are testing. In the second room we allow infestations to develop more naturally over a longer period.

These bugs are given access to a human host (me) every week or so, to provide nourishment and to elicit the natural foraging and harbouring behaviour. The current ‘infestation’ is around nine months old and has well-established harbourages, complete with faecal spotting, cast skins and eggs.

We use infrared time-lapse cameras to observe bed bug behaviour. This lets us see how bed bugs interact with monitoring devices or treated surfaces. Bed bugs are fussy about the surfaces they will walk over.

If a trap is performing poorly, we can usually see from the videos whether bugs are avoiding traps altogether or if they are entering and subsequently escaping. Details like this help to inform product development.

What have you discovered? Do you have any recommendations?

We recently worked with Engineering students from KTH Royal Institute of Technology, who are working on a monitoring device that attracts bed bugs with heat and carbon dioxide (CO2) released from a cylinder. Our infrared cameras allowed us to directly observe the effect of CO2 release on bed bug activity, allowing them to optimise release profiles.

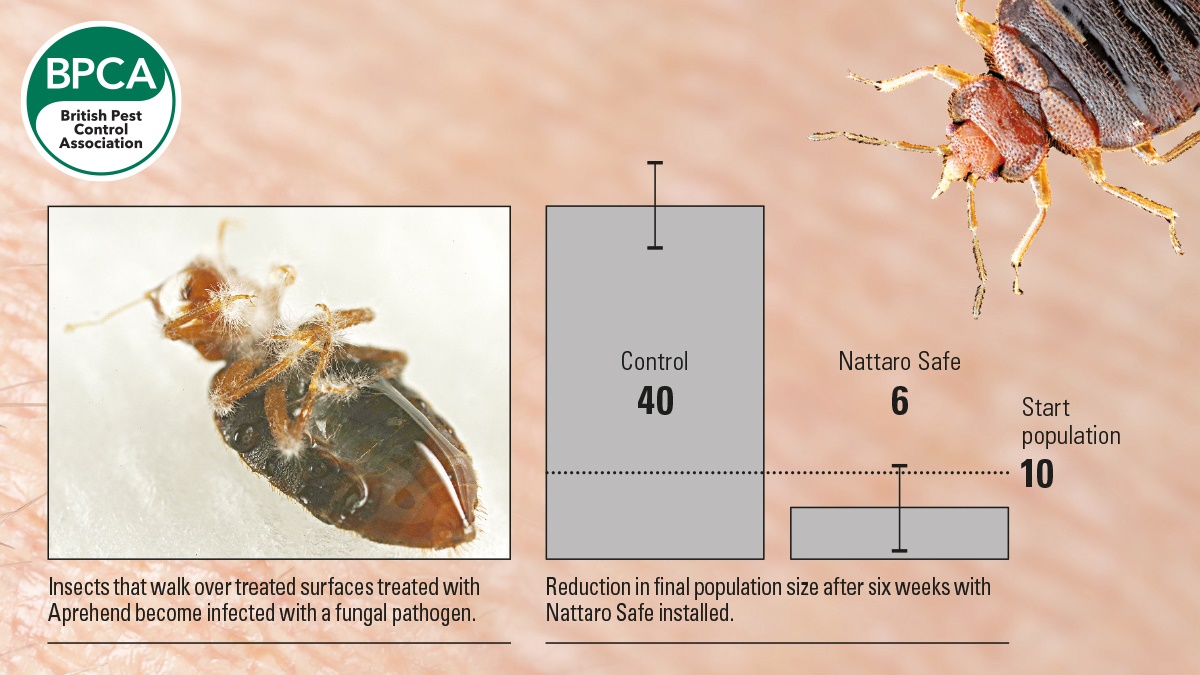

Last year we completed a study on Nattaro Safe (aka Insectosec Barrier Tape). This is a self-adhesive paper barrier tape containing diatomaceous earth (DE).

The tape is designed to be installed around sleeping areas as a long-lasting preventative measure against bed bugs. Ideally, the tape should be installed in such a way as to form a continuous barrier between the host's sleeping area and where the bed bugs tend to hide, which varies according to bed design. Hungry bugs easily cross the barrier in search of a meal, but in doing so, they cross through the DE-coated internal surfaces and subsequently die from desiccation.

The results of our study are very encouraging. Installing barrier tape on the underside of the bed frame resulted in an 86% reduction in the number of bed bugs present after six weeks compared to no-treatment controls. By the end of the trial, control populations were growing exponentially, while populations in rooms with barrier tape were in decline. Those bugs that did survive to the end of the trial were sickly and laid few, if any, eggs.

We are now evaluating Aprehend, a suspension of entomopathogenic fungal spores (Beauveria bassiana) from ConidioTec (USA). The spores are applied in narrow barrier treatments around the bed frame and legs using a small electric sprayer. Insects that walk over treated surfaces pick up spores and become infected with the fungal pathogen, usually dying in about a week.

The initial results of our trial look very promising! Aprehend is already popular in the USA and Canada and may soon be available to the European market via Andermatt Biocontrol Suisse.

Are bed bug numbers really soaring and spreading from Paris to London and beyond, as the global media suggested in late 2023?

It is a bit more complicated than that. There has been a recent increase, but let's put that into perspective.

The rise

Bed bugs evolved with cave-dwelling bats, and the transition from bats to humans probably occurred while early humans were still living in caves, thousands of years ago.

Egyptian pharaohs, Romans and ancient Greeks were all plagued by bed bugs, but the first record from the British Isles was not until 1583. They are believed to have arrived on cargo ships and were initially slow to spread due to the cool climate.

Bed bug activity is closely linked to temperature, which affects their development time, reproductive rate and mobility. Below 13oC, bed bugs become completely inactive, they stop feeding and their eggs don't hatch. So improvements to housing construction and heating, along with transportation, allowed bed bugs to establish and spread.

By the 17th and 18th centuries, they were common across the UK and, by the 1930s, nearly 11% of homes in British cities had them. There are reports that in parts of London every home was infested.

The fall

Between 1934 and 1943, efforts to clear slums and improve living standards drove bed bug infestation rates down. In the mid-1940s, the introduction of DDT and other organochlorine insecticides revolutionised bed bug control and, throughout the 1950s, bed bugs across Europe became increasingly scarce. For nearly 50 years, bed bugs were hardly known.

The resurgence

Towards the end of the 1990s, bed bug numbers began to increase in many parts of the world. Their success has been attributed to various factors, including low-cost travel and human population density. Many of the most potent insecticides have now been withdrawn on health or environmental grounds, and there is now widespread resistance to those that remain.

Impact of the pandemic

Covid-19 shut down the hospitality sector and restricted people's movement. Hotels, hostels and transport networks that had been battling bed bugs for years suddenly found themselves with a window of opportunity to tackle the problem.

By 2021, bed bugs had virtually disappeared from the hospitality and transport sectors. Data from the Swiss Pest Advisory Service in Zürich suggests that, in 2021, bed bugs reached their lowest level since 2013.

But bed bugs in residential sectors, particularly low-income and sheltered housing, were much less affected, and the impact of social distancing rules on pest management services probably exacerbated the problem. So, as travel restrictions were lifted in early 2022, bed bugs were quick to return to their old haunts. This post-pandemic bed bug recovery seems to be what triggered the late-2023 media attention.

In reality, outbreaks of bed bugs in Paris have no significance for the bed bug situation in London or elsewhere. Bed bugs have had a global distribution for centuries. Warmer environments facilitate more rapid reproduction, and high human population density facilitates their spread.

“Covid-19 shut down the hospitality sector and restricted people's movement. Hotels, hostels and transport networks that had been battling bed bugs for years suddenly found themselves with a window of opportunity to tackle the problem.”

What does the future hold?

Almost all professional residual insecticides approved for bed bug control are now based primarily on pyrethroids, but overuse of these compounds has resulted in widespread resistance.

In multiple occupancy buildings, where bed bugs easily move between rooms or apartments, this loss of residual efficacy allows them to keep re-infesting rooms that have already been treated, making building-wide control difficult to achieve with chemicals alone. In this situation, it is worth considering the options available.

Diatomaceous earth (including DE-barrier tape) can offer lasting residual protection. Efficacy can be affected by high humidity, so keep this in mind if you’re using it in conjunction with steam.

Bed isolation devices (eg Climbup Insect Interceptor) also help break the cycles of re-infestation and limit dispersal. Encasements for bed bases prevent bugs from hiding inside, where they are difficult to detect or treat. They also make future bed bug inspections and treatments much simpler.

Not every solution is suitable for every situation, but there is a growing range of tools available.