PPC116 | Technical

The recent Wild Animal Welfare Conference (WAWC) brought together leading experts and advocates, including BPCA President Chris Cagienard, to discuss the future of animal welfare.

Pest professionals and BPCA share many viewpoints with animal welfare academics, and their guidelines are being implemented in pest management strategies.

Here are five key lessons we can learn from this event and how they relate to the professional pest management industry...

1 Principles of ethical wildlife management

Nick Collinson from The National Trust introduced seven principles of ethical wildlife management, emphasising the balance between aesthetic considerations and nature’s realities. These principles guide more ethical and sustainable decisions in wildlife management:

- Begin by modifying human practices

- Justify with evidence

- Ensure objectives are clear and achievable

- Prioritise animal welfare

- Maintain social acceptability

- Conduct systematic planning

- Make decisions based on specifics, not labels.

These steps provide a useful and easily implementable framework for how pest professionals can consider animal welfare for every site.

|

2 Adopt a less human-centric view

One fundamental takeaway from the conference is redefining animal welfare by adopting a less human-centric view.

Decisions to cull animals should be based on their health and environmental impact rather than their categorisation as wild or domestic, sentient or not. This shift calls for a change in language, avoiding terms like ‘pest’ and ‘vermin’, which some speakers argue allows for inhumane treatment.

While we don’t agree that the word ‘pest’ is inherently wrong or justifies worse treatment, we all must try to better understand the interconnectedness of human, animal and environmental health.

For pest professionals, this translates into employing integrated pest management (IPM) strategies that prioritise non-lethal methods, habitat modifications and sometimes even the use of natural predators. Pest professionals already undertake to do this, showing that our industry already applies animal welfare practices.

|

3 Contextual wildlife management

Madeleine Campbell from the University of Nottingham emphasised that wildlife management must be contextual. There is no one-size-fits-all solution; each situation requires a tailored approach

based on ethical frameworks.

This involves defining ethical questions, understanding relevant laws and regulations, considering scientific evidence and expert opinions and acknowledging stakeholder interests.

The goal is to minimise negative welfare impacts and maximise positive outcomes for each species.

The professional sector is already taking this approach seriously by staying updated on legislation, conducting environmental risk assessments and tailoring site surveys to specific contexts.

|

“...moving animals to new habitats, often results in high mortality rates and may not be humane despite being perceived as non-lethal.”

4 Prioritise humane approaches

Adam Grogan from UC Davis stressed that any intervention, especially lethal methods, must be justified, effective, humane and part of a broader strategy.

Killing animals should not be the default response to perceived problems. Alternatives such as humane deterrents and habitat modifications should be prioritised.

For instance, the National Trust transitioned from lethal mole control, prioritising natural processes over aesthetic concerns.

Additionally, any lethal intervention must be continually reviewed to ensure it remains necessary and effective. For example, if moles attract rats, increasing the risk of leptospirosis, the non-lethal approach may need to be revised.

Pest professionals should discuss problem animals with customers, encouraging non-lethal control methods.

|

|

5 Balance lethal and non-lethal methods

The ethical and welfare challenges of lethal versus non-lethal methods were thoroughly discussed, with insights from Dr Julie Lane of the Animal and Plant Health Agency.

Translocation, or moving animals to new habitats, often results in high mortality rates and may not be humane despite being perceived as non-lethal. Additionally, live traps can cause significant distress, with animals engaging in intense escape activity.

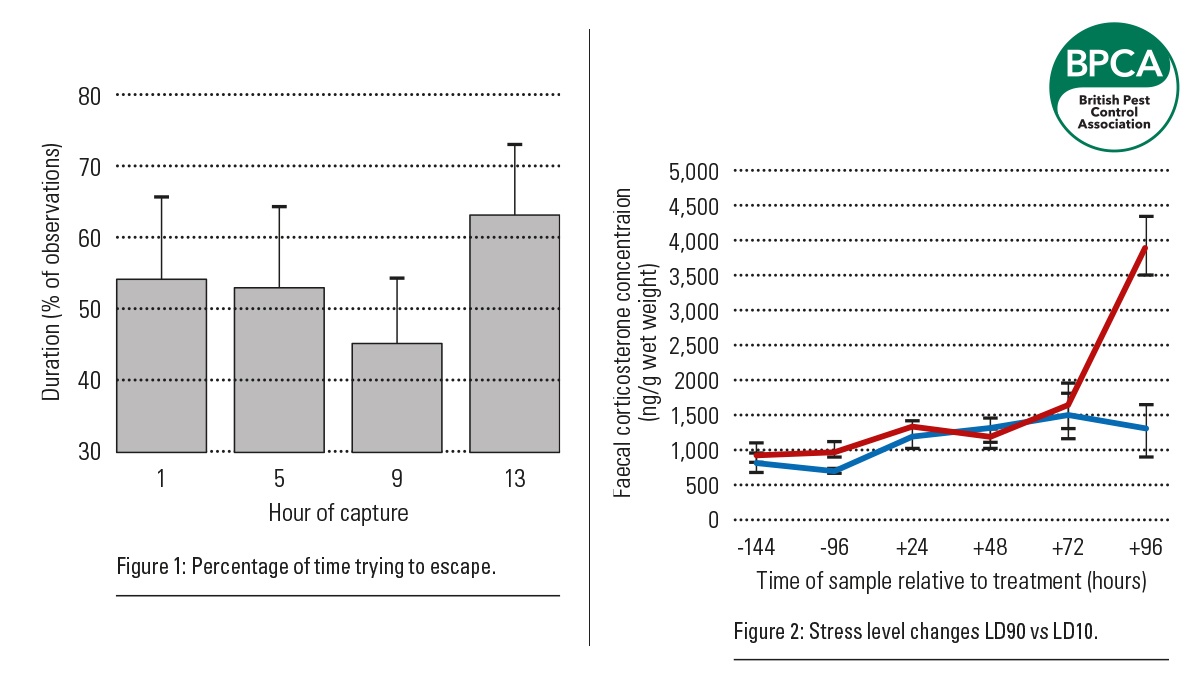

Poisoning, while sometimes necessary, must be carefully controlled to minimise distress. The duration of poisoning does not always correlate with distress, depending on the dose and method used (see figure 1).

Figure 2 shows that corticosterone, the stress hormone, increases slightly once a poison is ingested, with LD90 poisons causing a major spike in levels after three days. Meanwhile, stress levels tape off in animals affected by LD10 poisons.

Highly toxic poisons can cause more welfare issues and environmental risks, including secondary poisoning.

Effective wildlife management requires ongoing evaluation to ensure methods are humane, necessitating that pest professionals stay informed about new information in their toolkits.

The pest management sector has long argued that ‘humane’ catch-and-release pest control can be more inhumane than a traditional treatment option.

|

The Wild Animal Welfare Conference (WAWC) provided insights into the evolving landscape of animal welfare, highlighting the shared goals and practices between pest management professionals and animal welfare academics.

Chris Cagienard’s participation underscored the sector’s alignment with these progressive viewpoints. Integrating ethical considerations and humane practices into wildlife management is crucial.

While it might sometimes feel like pest management professionals and animal welfare organisations are at odds, none of us want to see animals suffer. We have a legal and ethical obligation to consider animal welfare while balancing the considerations with the risk to public health.