PPC117 | Technical

Deer have been an important ecological asset in our countryside for millennia. Red Deer (Cervus elaphus) and Roe Deer (Capreolus capreolus) are the only two species able to claim the United Kingdom as their true ancestral home.

Regular PPC contributor and rural pest expert Dave Archer explores how non-native deer species can affect the British countryside.

Deer are a great asset, whether by bringing pleasure to casual observers, gracing many areas from parklands to open moors, or being a valuable sporting benefit.

They also have the bonus of income from local accommodation, employment, sporting equipment and clothing sales, and venison sales in restaurants or meat sales outlets.

However, we now have a growing problem. We humans have inadvertently skewed the ecological balance in favour of deer (especially non-native species) in many ways by importing four other species of deer never previously found in these Islands.

The history of non-native deer in the UK

Once free, non-native deer found the British habitat to their liking and colonised many areas. They also found the land free from predators apart from man.

Previous inhabitants of our islands, such as wolves, lynx, and bears, relied on wild deer as part of their natural diet, keeping numbers stable to a certain extent and maintaining a reasonable balance in the ecosystem.

Additionally, injured, diseased, or older deer were naturally taken, and herds stayed comparatively healthy.

During Roman Britain, Fallow Deer (Dama dama), which were previously absent, were viewed as a beast to hunt and eat and were imported into many areas of the British Isles.

In fact, their place in the fauna of these isles is now so well-rooted that they are accepted as part of the natural ecosystem.

These are the large “spotted” deer with huge palmate antlers found adorning country parks and estates, as well as well-established herds in the wild. Often albino deer can be found in these herds.

In fact, pubs called the White Hart (Hart meaning deer), of which there are many, can be directly attributed to this point.

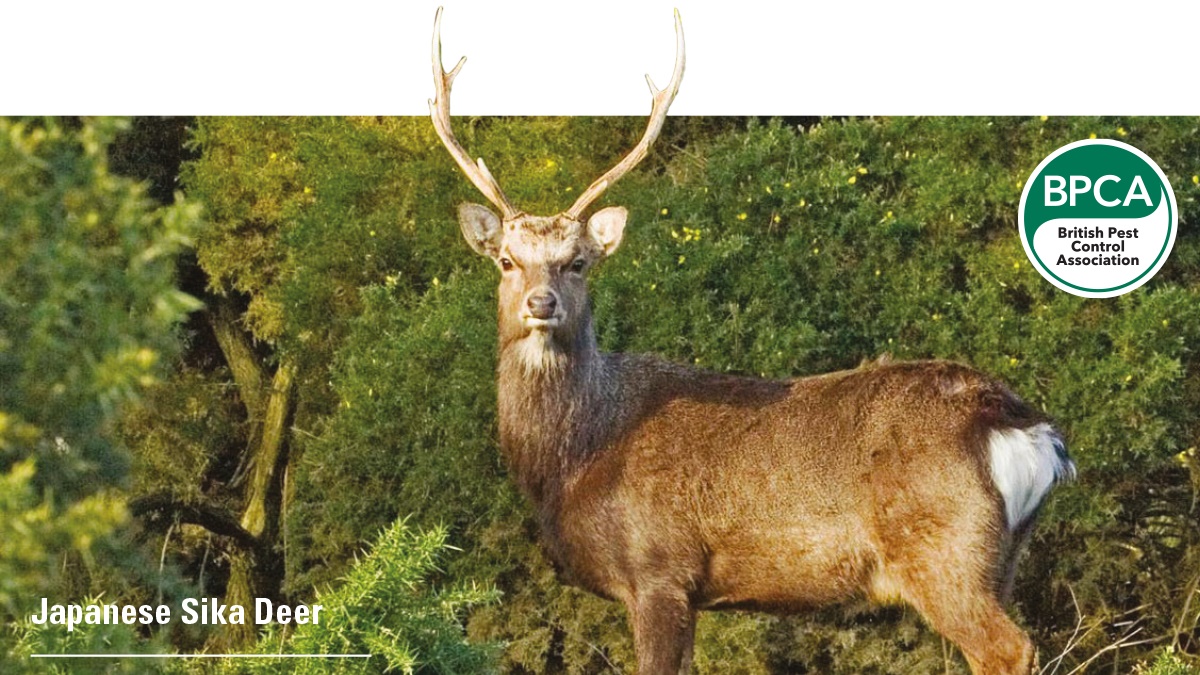

In around 1860, Sika Deer (Cervus nippon) were introduced into Britain and well-established herds are now widespread in Scotland, with patchy populations in England and Ireland.

Hybridisation with naturally occurring Red Deer is now occurring much more frequently, and brings its own problems of maintaining pure genetic strains of wild Red Deer.

Red, Fallow, and Sika Deer are herding deer, forming large travelling groups. Roe do join together in groups for the winter period, but these will naturally disperse by late spring and generally are nowhere near the size of herding deer numbers.

Modern invasive species

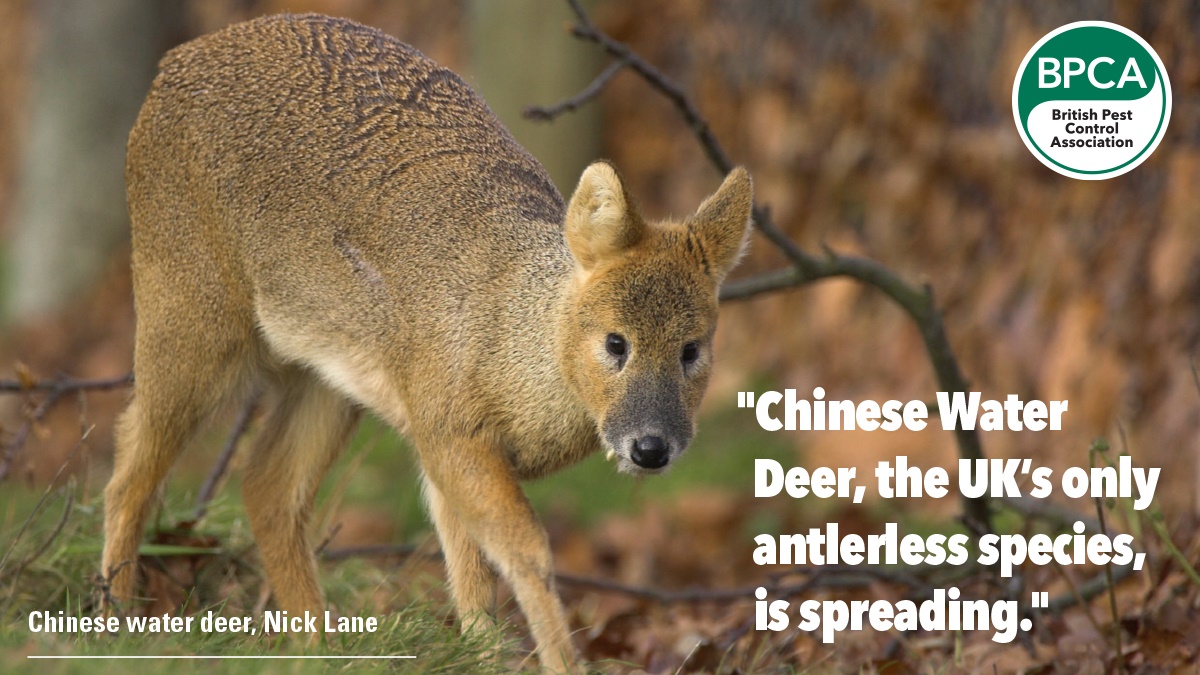

In the past hundred or so years, we have introduced Reeve’s Muntjac (Muntiacus reevesi) and Chinese Water Deer (Hydropotes inermis)- incidentally, the only species in the UK without antlers.

Muntjac, in particular, is responsible for many motor vehicle accidents per year, and being the only species able to breed all year round, it is expanding its range across the country at an alarming rate.

Figures suggest Muntjac deer populations have doubled in recent years and have a capacity to live very close to and even within urban settlements. Their small size allows them to capitalise on areas inaccessible to other deer species. Both species are in the main solitary.

Muntjac are found in native woodlands. Being such a small species (around the size of a medium-sized dog), their intense browsing habit means that the lower levels of woodland and scrub are laid open to prevailing winds, making the areas unattractive to low-level nesting birds such as nightingales and woodlarks.

Scarce wildflowers and orchid numbers can be irreversibly damaged if deer populations remain unchecked.

Many Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSIS) are often now recorded as being in less than ideal health due to the impact of non-native deer.

Invasive deer management

Of course, we must not treat these imports as pests, such as Grey Squirrels or Glis Glis. All deer must be respected, although control is absolutely necessary to preserve farm crops and undergrowth in woodland or where sensitive nesting sites are discovered.

Deer cannot self-regulate, and if numbers are left unchecked, deer can suffer from injury due to disease, age-related issues and over-population.

We certainly are not looking to eradicate populations but to manage them to the best of our ability and for their long-term health benefits in the absence of natural predation.

From a human welfare perspective, zoonotic diseases such as Lyme Disease can cause serious long-term effects if left untreated, and human fatalities and injury from deer collisions with motor vehicles are a very real problem.

If you live in a rural area, how many deer have you seen dead by the side of the road after a vehicle impact? It was not only the deer that sustained damage!

The only legal method of deer culling is by use of a suitable centre-fire rifle deployed by suitably trained and authorised persons.

Deer are subject to legal constraints in relation to:

- Times of day

- Times of year they may be culled

- Sex

- Species.

However, in some areas, this is not a practical solution, so other methods of deterring or excluding the deer must be found, such as deer-proof fencing or repellents.

Although these solutions may work in small areas, the expense and practicality of deploying such methods in large rural areas are totally prohibitive.

Perceptions of deer stalking

The world of deer stalking and management is very different from when I started this work in the 1980s. I make no apology for stating that the general public’s perception of deer is, in the main, skewed in favour of the deer by personalities or certain organisations who, either by intent or ignorance, have little or no idea of the problems caused by deer or how best to control them.

Emotions are the overriding factor when dealing with a practical problem. A well-placed shot from a rifle is instant.

The animal never suffered the stress of an abattoir, nor from medical intervention to end its life.

It lived life in a free-range environment and the end product (venison) is enjoyed as a very healthy and tasty meal.

Perhaps we should question why more advertising isn’t done to promote these facts, as opposed to the obsession with fast- food chains and meals delivered packaged to your door within minutes?

And I feel that is the problem. We have distanced ourselves from the reality of the countryside, and the management of animals; relying instead on convenience and comfort.

We may have learned the error of our ways in relation to importing invasive mammalian species, but in general we are now evermore detached from the realities of the great outdoors.

Like what you read?

Dave will return next year with a follow-up article on deer management. He will explore the world of our native deer species and how you can become professional and qualified in deer management.